China is not without its problems, but, given the sheer scale of opportunities, warrants far more than peripheral market status for equity investors, argues Jian Shi Cortesi. She believes investors should look through the lingering anti-China haze and instead focus on the powerful longer-term growth story.

12 December 2023

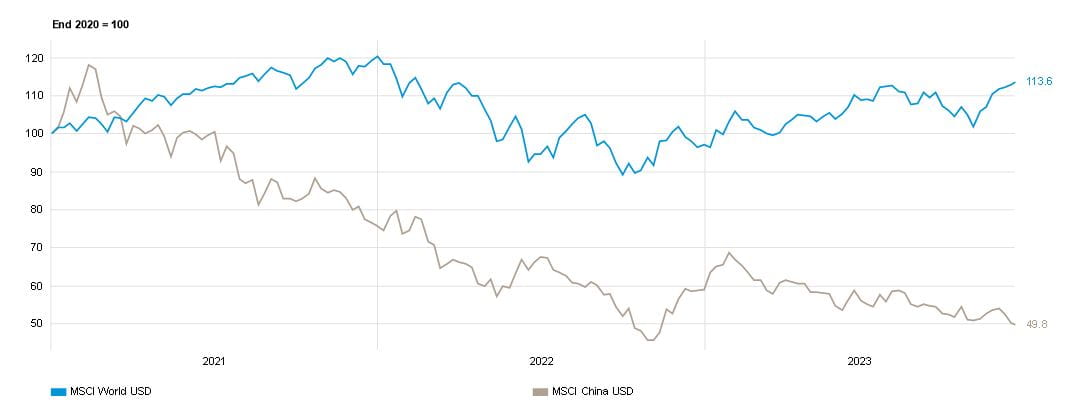

While global stock markets have performed surprisingly strongly this year – flying in the face of geopolitical worries and elevated interest rates – China has been a notable exception. The MSCI AC World index climbed by 18.0% in USD terms over the first 11 months of 2023 (to end of November). Meanwhile, the broad-based MSCI China A index has actually fallen by -9.0% over the same period.

There are many explanations for this dramatic underperformance, some more credible than others. In our view, by trying to sort the fact from the fiction, investors stand to get a better handle on whether the falls are truly justified by the fundamentals, or whether other short-term factors may have distorted the picture, potentially highlighting rare and attractive opportunities for investors.

Chinese equities have sharply underperformed their global peers since early 2021

From 31 December 2020 to 11 December 2023

Past performance is not an indicator of future performance and current or future trends.

Trade tensions have fed the anti-China narrative

In our view, the boiling over of US-China trade tensions, which had been simmering for years previously, have played a part in distorting many investors’ view of China. Western investors are more likely to read news through the prism of international media outlets rather than having direct access to local-language providers. And therefore I think there is a degree of bias in some popular news outlets, painting a picture that makes investing in China altogether less appealing for many than it really should be. Whatever the explanation, the reality is that, while the US, European and Japanese stock markets are seen as core holdings for many investors, China is all too often relegated to peripheral status. While some investors may gain a degree of exposure through global or emerging market funds, many do not have any meaningful direct exposure to China. And that could mean investors – many without access to the accurate picture that might help them make an informed choice – could be missing out on what we think is a rare and compelling structural growth story.

Retail investors sit on their hands but value and inside buyers step in

That said, it could be argued that China’s domestic retail investors are hardly flying the flag for their own market nowadays. Over much of the previous two decades, many became used to the economy growing at a breakneck 6%-10% every year and took quick and easy stock market gains for granted. Now, with the economy growing more slowly – albeit at rates many developed economies would envy – and the stock market languishing, Chinese retail investors have been largely inactive. China’s domestic market is 80% driven by retail investors, with a holding period sometimes as short as a week, hence the market is treated by some as more of a casino than a long-term investment. However, value-driven buyers are stepping in, and, unusually for China, corporates have initiated share buy-backs this year, taking advantage of what they must see as cheap valuations. Meanwhile, Chinese sovereign funds are also buying.

Economic growth is slowing, but remains robust – an enviable trend in a global context

For all the talk about China’s weak economy, growth for 2023 is likely to hold around 4-5%, a level I believe is realistically sustainable over the medium term. After all, in economic terms, China has come a long way already; it is no longer a teenager, more of a young adult, now heading towards active and healthy middle age. So as the economy matures further, perhaps in a decade or so we might expect growth to settle closer to 3%.

What are the short-term drivers – and brakes – on growth?

First, for all the positives, we need to recognise that the country undeniably faces some short-term challenges. At present, the main drag is the real estate sector. In China, unlike many other countries, concerns centre on developers rather than homeowners struggling to pay their mortgages as borrowing costs have risen. Given China’s supply glut of new residential property, the rate of new building needs to slow sharply, until demand takes up the slack. Naturally, the consequence is that some developers will continue to go out of business, especially those with the most debt. Sentiment around these companies remains so poor that their woes are dragging on the market, putting off would-be buyers. Compared to their peaks of 12-18 months ago, property prices in China are now around 10% lower, and lower still in some small towns. Construction activity today is much weaker than two years ago, with the obvious drag effect on overall economic growth. To confound the short-term malaise, the widely forecast post-lockdown rebound in consumer spending has failed to fully materialise.

Standing tall in the face of export headwinds

Another headwind to growth is exports, not just for China but also for Korea and Taiwan. This is partly attributable to muted demand from the US and Europe, but also to tech-specific factors. Lockdowns in 2020-21 pulled the demand curve forward as homeworkers clamoured for new laptops, screens and printers, as well as TVs and mobiles. We have since seen a resulting down cycle in demand for this kind of tech hardware, with a slowdown in the semiconductor sector. There has also been some effect of low-end manufacturing moving out of China to lower-cost countries, such as Vietnam and India; this has been happening for the last decade but is now picking up pace.

Yet, even in the face of the headwinds from the real estate and export sectors, China’s economy is still growing at a rate that would be the envy of much of the developed world.

iPhones: how China is moving quickly up the IT value chain

If an average iPhone sold for USD 600 a decade or more ago, with the country’s key appeal to global corporates being access to cheap labour, China’s economic ‘take’ from the low-value assembly work might have been a meagre USD 10. Nowadays, China’s slice has grown tremendously, largely as a result of domestic companies now supplying many of the key components, like touch screens, fingerprint sensors and camera modules. And if China can supply the beating heart of the device – the semiconductor – then its take could rise to around USD 400, or two thirds of the iPhone’s sales price. This prospect could partially explain why the US has been clamping down on semiconductor supply to China. Simultaneously, China – both at government and corporate level – has been investing heavily in semiconductors, pushing for a breakthrough that could capture an ever-larger share of the value chain for companies like Xiaomi and Huawei. In fact, China may well have already achieved this breakthrough – in September Huawei raised eyebrows with the launch of the new Mate 60 Pro flagship handset featuring the Kirin 9000S, a powerful state-of-the-art processor with components for 5G connectivity seemingly built in. This evident breakthrough demonstrates how China is moving to capture value at the cutting edge of tech development and manufacturing. As a consequence, this creates higher-paying jobs that should eventually filter through to boost consumption in China.

Broader theme of technology self-reliance

China’s push to develop advanced microchips domestically does not stop with the chips themselves; the country is prioritising the development and production of machines used to make the chips, a segment dominated by specialist Western companies, such as Dutch firm ASML. And while Western media focus on near-daily advances in artificial intelligence (AI) by companies like OpenAI, Google and X, major Chinese companies, such as Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, are launching powerful AI solutions of their own. The same themes are developing rapidly in medical technologies; the days of Chinese medical device makers supplying only gloves and masks are long gone, with Chinese companies now at the forefront of developments in artificial limbs and AI-driven body monitoring technology.

Pushing ahead elsewhere in advanced manufacturing

For as long as most of us can remember, Boeing and Airbus have dominated global commercial airline production. But this year, Shanghai-based Comac launched the C919, a narrow-body passenger jet. With Western giants all but shut out of China’s market by trade restrictions, state broadcaster CCTV reports that the C919 has already won over 1,500 orders from the likes of China Eastern Airlines. And with shipments of Boeing’s 737 MAX still delayed following fatal crashes, Comac is already taking advantage of international sales opportunities, for example, recently concluding a deal to sell 15 C919s to Brunei’s Gallop Air. Elsewhere, China is already a powerhouse in electric vehicles (EVs) and is set to be confirmed as the world’s biggest car exporter this year. While China’s growing dominance is not yet fully apparent in Germany, France, Italy and the US – where governments would likely work to protect their domestic manufacturers, Chinese EV brands are rapidly winning market share in countries lacking a ‘flagship’ car brand, such as Brazil, Australia and Russia. And beyond transport-related industries, China’s leading role in producing infrastructure for the energy transition is widely acknowledged, with robotics playing an ever-more important role in Chinese manufacturing.

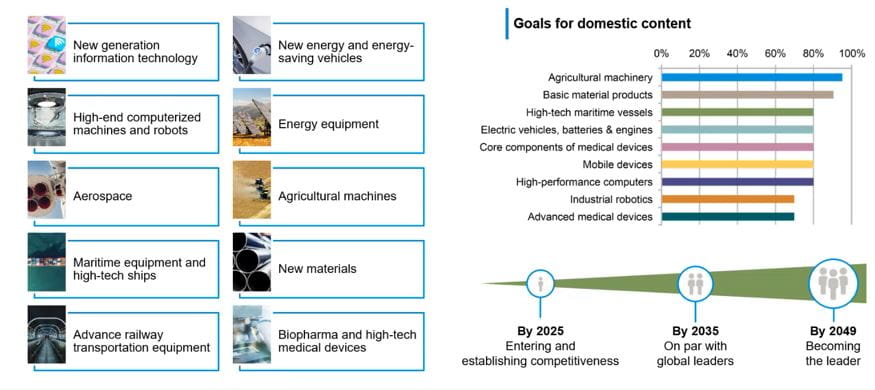

‘Made in China’ initiative: taking centre stage for decades to come

Launched in 2015, China’s overarching long-term plan set a target of 2025 for the country to establish itself as a competitive player on the global stage in all of the aforementioned industries, as well as sectors such as advanced railway systems, maritime infrastructure and new-generation agri tech. By 2025, China aims to be on a par with global leaders, and by 2049, to be the undisputed champion in 10 key sectors. Although China’s authorities no longer trumpet the Made in China initiative the way they once did, perhaps with view to avoid inflaming US trade tensions with talk of future global domination, the initiative is progressing in line with the long-term plan. In our view, further progress on a multi-decade timescale will be a major driver of sustainable GDP growth, with the associated income growth bolstering domestic consumption.

"Made in China" 2025 / 2035 / 2049

The "Made in China" 2025 plan highlights 10 sectors

In the meantime, China’s backtracking from recent over-reliance on real estate construction is likely to meet further bumps in the road, and there is no denying that the ups and downs could make for an uncomfortable ride for sectors beyond property in the near term. But China is not looking for popular short-term wins that might entail long-term downside. Rather than pursue the sugar-rush economic policies that some countries have implemented over recent years, the Chinese authorities are instead targeting realistic yet highly attractive rates of economic growth over the long term and are progressing with their plan to transition the ‘largely emerged’ superpower towards a high-skill, high-wage economy. With the strategy already delivering results in key sectors as Chinese companies build market share in industries shaping the future, and subdued short-term sentiment already fully reflected in valuations, we think investors overlooking Chinese equities risk missing out on long-term structural growth opportunities.

The information contained herein is given for information purposes only and does not qualify as investment advice. Opinions and assessments contained herein may change and reflect the point of view of GAM in the current economic environment. No liability shall be accepted for the accuracy and completeness of the information contained herein. Past performance is no indicator of current or future trends. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice or an invitation to invest in any GAM product or strategy. Reference to a security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. The securities listed were selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the themes presented. The securities included are not necessarily held by any portfolio or represent any recommendations by the portfolio managers. Specific investments described herein do not represent all investment decisions made by the manager. The reader should not assume that investment decisions identified and discussed were or will be profitable. Specific investment advice references provided herein are for illustrative purposes only and are not necessarily representative of investments that will be made in the future. No guarantee or representation is made that investment objectives will be achieved. The value of investments may go down as well as up. Past results are not necessarily indicative of future results. Investors could lose some or all of their investments.

The foregoing views contains forward-looking statements relating to the objectives, opportunities, and the future performance of the U.S. market generally. Forward-looking statements may be identified by the use of such words as; “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “should,” “planned,” “estimated,” “potential” and other similar terms. Examples of forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, estimates with respect to financial condition, results of operations, and success or lack of success of any particular investment strategy. All are subject to various factors, including, but not limited to general and local economic conditions, changing levels of competition within certain industries and markets, changes in interest rates, changes in legislation or regulation, and other economic, competitive, governmental, regulatory and technological factors affecting a portfolio’s operations that could cause actual results to differ materially from projected results. Such statements are forward-looking in nature and involve a number of known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and accordingly, actual results may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. Prospective investors are cautioned not to place undue reliance on any forward-looking statements or examples. None of GAM or any of its affiliates or principals nor any other individual or entity assumes any obligation to update any forward-looking statements as a result of new information, subsequent events or any other circumstances. All statements made herein speak only as of the date that they were made.