Global long-dated bond yields have jumped in recent weeks. This increases the cost of capital for economies and corporations. The main culprit is the US spending bill. Can it be reined in?

17 June 2025

Something has been stirring in the otherwise sedate world of the 30-year global government bond market, with profound implications for investors. In late May, a weak auction for US Treasuries precipitated a sharp sell-off not just in long-dated bonds but also stocks in the US and elsewhere.

Why do stocks care about the bond yields? Because yields effectively serve as the discount rate by which the price of a series of future earnings streams - what stocks essentially are a claim to - is determined. Put simply, if bond yields go up stocks should, all other things being equal, go down and vice versa. The economy also cares about bond yields because they influence mortgage rates and the cost of corporate borrowing. So, the prospect of higher bond yields matters a lot for market participants. The key questions now are: what has been driving the sell-off in long-dated bonds that triggered the correspondingly higher yields, and what might bring them those yields back down in the future?

Vigilantes return - global long-dated bond yields have jumped:

Chart 1: Change in 30-year government bond yields, % points

(From 31 December 2024 to 9 June 2025)

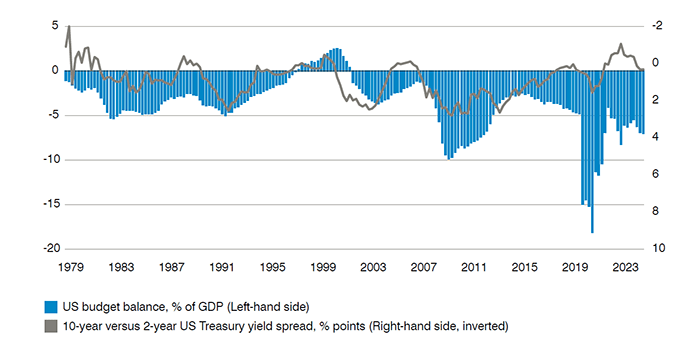

The main cause behind the recent surge in long-dated yields has been the US government’s borrowing position. President Trump’s “Big, beautiful bill” was passed by the US House on 22 May by a single vote, before going to the Senate for approval by 4 July. The tax bill is projected to increase government debt by trillions of US dollars over the next decade and was arguably why the US lost its AAA credit rating recently. Even before the new bill gets passed, the US government had already borrowed around USD 2 trillion over the last year, equivalent to 6.9% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The Congressional Budget Office now forecasts the deficit will reach 7.3% of GDP by 2050. By way of context, the average size of the US budget deficit as a percentage of GDP since 1980 has been just under 4%. Indeed the deficit today has never been so extended outside a recession, a fact which brings its own unique risks.

Traditional Keynesian demand management always saw government expenditure as something to be raised primarily in recessionary times to ‘smooth out’ the economic cycle. But today with the US economy close to full capacity (see the low unemployment rate of 4.1% and inflation still above target at 2.3%), more borrowing and stimulation of the economy will only add to potential inflationary pressure. Needless to say, lenders to the US Treasury (ie bondholders) have balked at all this, hence the higher yields demanded from its bonds.

Will only get worse - US budget deficit already extended:

Chart 2: US budget deficit (From 31 Dec 1979 to 31 Mar 2025)

It should be remembered that bond yields everywhere have been rising, and while the US bond market is a strong influence, other countries’ bond yields have been climbing for their own reasons, even if some of those reasons chime with the US experience.

In the UK and Japan, inflation has been unexpectedly heating up. UK Consumer Price Index (CPI) hit 3.5% in April (a full 1% point higher than the previous month’s reading) while Japan saw the exact same figure for its core inflation reading. For the UK, this presents genuine economic risks. The economy is stagnating, and the Bank of England would prefer to cut rates, but a 3.5% inflation reading cannot be dismissed so easily. 30-year gilt yields have climbed above 5%, not far from their peak during the calamitous Truss government of 2022, so the implications for Britain’s already tight fiscal position are potentially serious.

For Japan, higher inflation was always something to be coveted after so many years of virtually no price rises, but these figures will be making for awkward conversations at the Bank of Japan, where the “price stability target” is 2%. Policymakers will be keen to avoid a repeat of last summer’s poorly received rate hike and Governor Ueda has spoken of making policy adjustments only “as needed”. And, just as with the UK (and the US for that matter), the fiscal position is problematic, with Prime Minister Ishiba recently telling parliament that it is worse than Greece’s.

For Germany, the rise in yields is arguably more benign. Following Chancellor Merz’s announcement that significantly more would be invested in Germany’s crumbling infrastructure and disproportionately small army, higher yields can perhaps be interpreted as reflecting high future GDP growth rather than a risk premium (as in the US and UK) or inflation (as in the UK and Japan). This separates ‘good’ borrowing from ‘bad’ in a sense, but overall, it is cold comfort because a higher cost of capital mathematically implies lower prices for assets - including of course stocks. Little wonder then that global stock markets took so poorly to the spike in long-dated yields, and only recovered their poise when said yields came back down again from late May.

What might offer a more lasting resolution?

At this point it’s important to consider what could alleviate the situation more permanently.

From a technical perspective, slowing the issuance of long-dated government bonds could provide respite, and this is happening in the US, and potentially being considered in Japan. But it doesn’t fix the underlying issue of too much indebtedness amongst the world’s major economies (Germany excepted). This has been putting lenders off long-dated bonds, and driving yields higher. And herein lies the potential fix because higher yields could prove self-resolving. Cost of capital does genuinely matter for the Trump administration, as evidenced by the President’s outburst on Truth Social in early June in which he demanded that “Powell must now LOWER THE RATE. He is unbelievable!” Republicans are also aware of the importance the bond market’s sensitivity to debt levels, as revealed by their attempts to argue that the higher economic growth resulting from the spending bill will generate more revenue. Neither of these efforts seem convincing. If bond yields do jump again as the Senate’s 4 July deadline for passing the bill nears, it could result in said bill quickly being dampened down or renegotiated.

One theory currently doing the rounds is “Trump Always Chickens Out” (TACO), which has already been partly demonstrated during the tariff negotiations. In the case of the spending bill, bondholders wouldn’t even bother negotiating like America’s trading partners do - if they don’t like what they see they will simply ditch US paper (thus propelling yields upwards) until something changes. This is likely the best prospect for a more lasting resolution to the issue of the spending bill, although there is of course no hard guarantee that the administration will back down. For investors whose nerves remain frayed by Liberation Day, it all makes for a challenging start to the usually quieter summer season. Reliable portfolio diversification may still be required.

Julian Howard is Chief Multi-Asset Investment Strategist at GAM Investments. This article represents the views of GAM’s Multi-Asset team.